So this is technically my first article ever posted to Substack, not that the world needs another Substack article to read, and honestly, my original hope was to post a “why does my opinion matter” article before putting out any real content. However, no one ever reads those anyway, and, more importantly, this article seems timely given that bank 2Q earnings season is already underway it’s already shaping up to be more interesting than most.

I feel like I should add a caveat before you read any further that the concepts discussed here can get a little convoluted. Someone who took a look at this before publishing noted that it might take someone with a basic idea of the mechanics of bank balance sheets to conceptualize the notions discussed below. So, that’s to say this essay may not be for everyone (or anyone for that matter, I could just be rambling to myself here), but if you’re interested in this sort of thing, I hope the ideas below are thought-provoking.

Nice Little Bank

The reason for drafting this entire piece was because while I was doing due diligence on (another) small, publicly traded bank I noticed a trend I had seen numerous times in the past couple of months. So, while the details below do actually pertain to a real bank, the theme is indicative of a much broader set of community banks across the country (hence the title of this article).

In doing research for a good investment opportunity, I came across a nice little bank, which over the course of its history has generated good risk-adjusted returns, a good dividend, and a steady earnings flow. For the duration of this article, I will refer to them as NLB (Nice Little Bank). To give you a little more context, NLB had about $1.5bn in assets, funded mostly by deposits and equity, with some overnight repo and Federal Home Loan Bank borrowings as well.

Between 2014-20191, NLB posted an average ROE2 (Return on Equity) of ~10.5% on an Efficiency Ratio (operating expenses divided by net interest income plus fee income) of ~64%. During this time, NLB had average annual loan growth of ~9% on top of average deposit growth of 4%, and given that deposits usually drive bank balance sheet size, the average asset growth for NLB for this period was around 4.5%. Normally, loan growth outstripping deposit growth isn’t a great sign of balance sheet health3, however, in this case, it wasn’t as bad as it seems because NLB was in the uniquely beneficial position in the community banking world of having a low loan to deposit ratio.

Sidenote: As a community bank, you live and die by your ability to maintain and service your deposit base, and given that an overwhelming majority of legacy community banks have been built on a thrift-like model, they had to look toward high-cost deposits in order to fund their loan growth. Historically, the thrift model thrived on the ability to pay up for deposits because the left side of their balance sheet was filled with long-duration mortgage loans originated during a time when the yield curve actually had some steepness to it and you got paid for the duration you were putting on your books. This model has fallen by the wayside due to a myriad of factors with the most important being (essentially) free government money in the form of quantitative easing, which has thus culminated with the Federal Reserve now owning somewhere in the neighborhood of 30% of the mortgage-backed securities market.

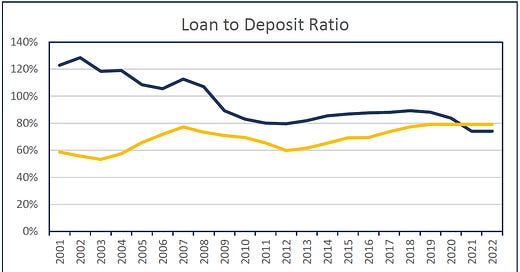

Back to NLB, as you can see in the above chart above NLB has historically run below market peers (in this case banks with assets between $1-10bn) in their loan-to-deposit ratio (LTD ratio). However, they have been converging with peers in this category consistently since 2011 and eventually exceeding their peer LTD ratio in 2021. In good times, this is a healthy thing for a community bank as it usually drives a higher Net Interest Margin given that yields on bank loans (for the most part) are higher than those on their securities or cash portfolios. Therefore, the ability to redeploy lower-cost funding from deposits (versus FHLB borrowings) into higher-yielding loans, results in higher returns on capital.4

Below you can see, that their “sticky” deposit base has resulted in a slightly lower than peer cost of deposits in times of higher rates and slightly higher cost of deposits than peers in times of low rates. While this is not a tremendous sign of pricing power, it does show that they are not leading with rate to attract deposits in the door.

Another positive for NLB is that they seemingly avoided taking undue credit risk over the years which has resulted in a net charge-off ratio materially lower than the peer average (shown below).

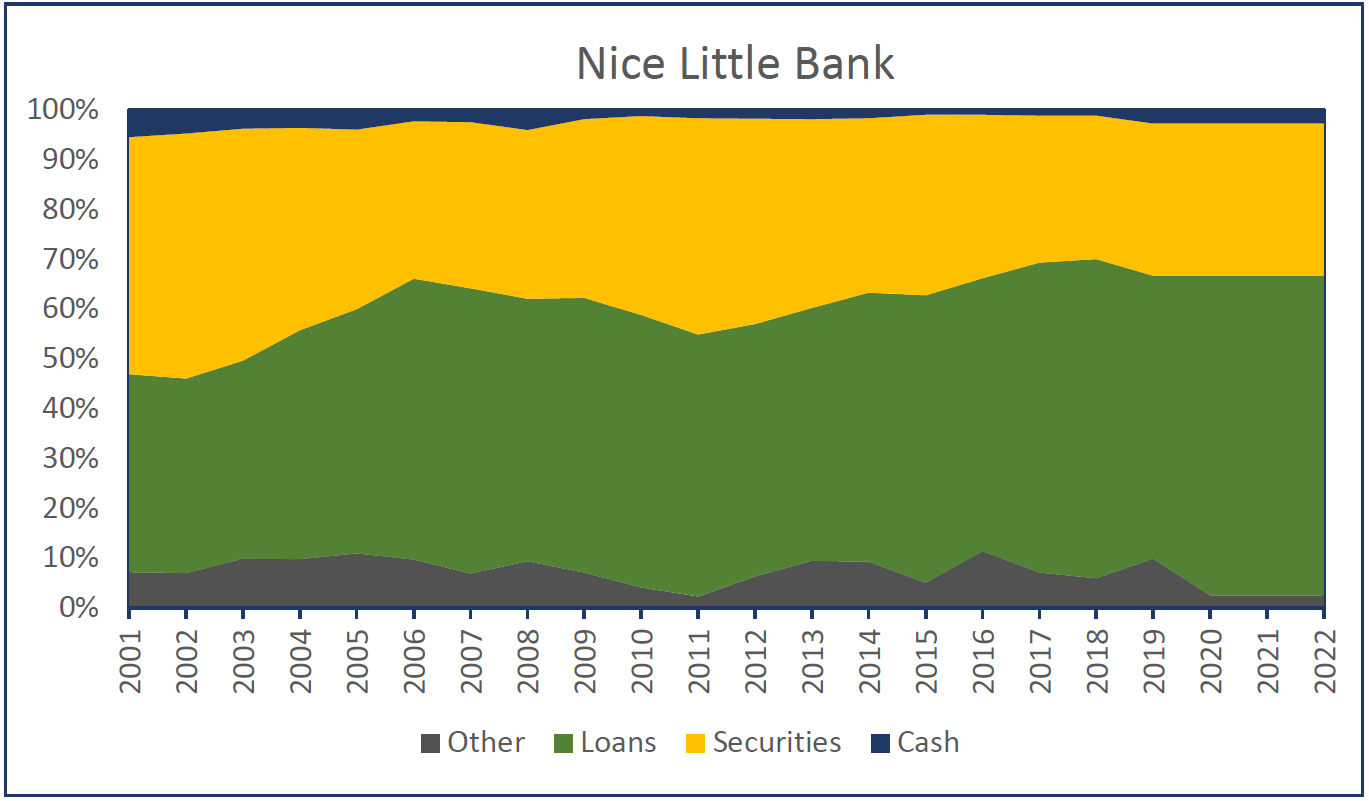

On the asset side of the balance sheet, however, as we discussed above, a large deposit base without tremendous lending opportunities led to a substantial securities portfolio and remarkably low cash buffer relative to asset size.

For reference, here are the same metrics for peer banks.

For context, however, it would be irresponsible to not discuss the monetary policy environment of the past 15 years, which has been uniquely favorable for the fixed income environment. In simple terms, the Federal Reserves’ balance sheet has been used, since the emergence of the 07-08 crash, as an experiment to artificially quell bouts of volatility, which has had the effect of materially deflating bond yields. By inflating the size of the balance sheet by more than 12x since the beginning of 2003, the Fed has successfully propelled the most favorable fixed income market in history through open market purchases of US Treasuries and Mortgage-Backed Securities. As shown below, even when they had seemingly stemmed the tide of their quantitative easing experiment in 2018 and began to chip away at the MBS portfolio, they soon had to reverse course and be a liquidity backstop for the market during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. As a result of this market intervention, the Fed has managed to pull down long-term securities yields and thus increase the prices of those bonds.

Earlier this year, the Fed announced that they would turn off their monthly securities purchases and begin to reduce the size of the overall balance sheet (again) through both natural amortization and open market sales. Since the beginning of the year, the US 10-Year Treasury Yield has more than doubled and the balance sheet today is still $134bn larger than it was on 12/31/2021.

I should note, that hindsight here is 20-20, and despite all the criticism that the Fed receives, the injection of their liquidity through the Global Financial Crisis and during the depths of COVID-19 pandemic successfully settled market volatility and reinstated stability. However, the longer-term impacts of the unwinding of this liquidity infusion around have yet to be determined.

The reason that this is imperative to discuss is that the Fed’s actions have depressed market yields, which has ultimately led to compressed Net Interest Margins for the banking industry. However, for banks like NLB, where there are limited lending opportunities, they have resorted to purchasing these low-yielding, long-duration securities because they are higher-yielding than cash and more liquid than syndicated purchased loans. Because of an accounting rule, only the securities held in a bank’s Available for Sale (AFS) portfolio get marked on the balance sheet, while securities tucked away in their Held to Maturity (HTM) portfolio do not need to be marked quarterly. The reason to hold them in AFS is that it is a lot easier to sell them during a liquidity drawdown, so banks for the most part hold AFS securities rather than HTM. Just to clarify though, putting them in the HTM bucket does not make the securities any more or less valuable, they just simply do not need to be marked on the balance sheet every 3 months. The marks to this AFS portfolio though, are fed into a bank’s capital position through the Cumulative Other Comprehensive Income (OCI) line not through Net Income, because remember they have not realized these gains or losses by selling them.

We are now seeing the effects of higher rates impacting bank OCI in a meaningful way. In 1Q2022, the 10yr UST yield increased from 1.53% to 1.92%, and using FDIC data, banks saw the single largest negative mark on their OCI portfolio since the data has been recorded. In a single quarter, the banks wiped out $139bn in equity capital from marks that impacted their OCI portfolio. During 2Q2022, the 10yr UST yield increased further from 1.92% to 2.89%… How do we imagine this is about to play out? In just under a month around five thousand regulated depositories will release their 2Q2022 Call Report information and you can expect material losses on their OCI portfolio to continue to compress equity capital.

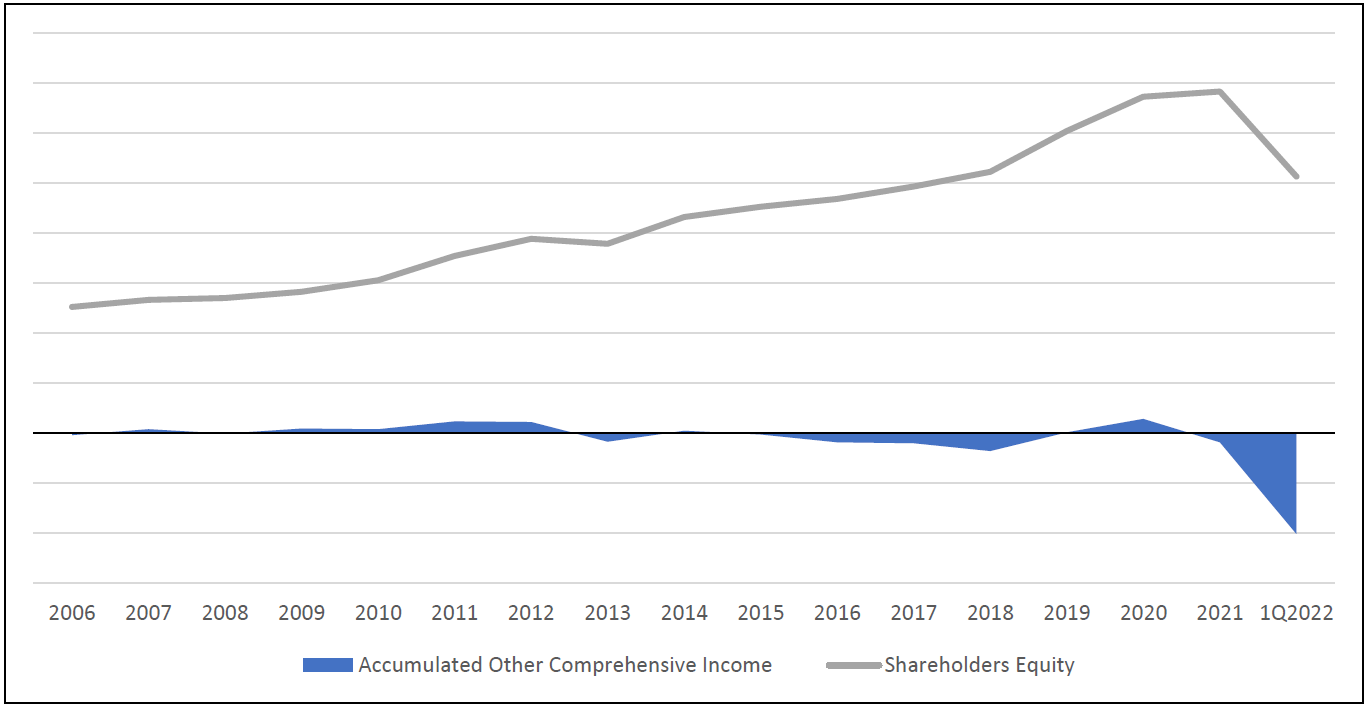

Bringing us back to where we started, we have a Nice Little Bank that between 2014-2019 had an ROE of 10% and paid about half of that out in dividends, resulting in 30% tangible book value growth. They have a solid legacy deposit base that has been growing about 4% and a loan portfolio that has grown over double that pace. While the loan portfolio has grown, they have used a large securities book to manage their Net Interest Margin, which worked while rates were low but as rates have risen in the past 3 quarters, NLB has run into some troubles. As shown below, total shareholder equity for NLB dropped 25% in Q1 and is now below 2018 levels.

This has resulted in an equity to assets ratio (no intangibles or preferred equity so this is the TCE ratio) of below 6.5% and I can guarantee that this number is not going up in 2Q2022 based on the conversation above. This means the cushion on their balance sheet for potential loan losses in excess of their reserve has shrunk dramatically.

One benefit that community banks have in this environment is that the equity to assets ratio is a GAAP calculation and regulatory capital ratios are not impacted by hits to OCI. Therefore,f when looking at NLB’s Tier 1 and Risk-Based Capital ratios, you would have no idea that the AFS portfolio marks have driven down book value by 25% (NLB’s regulatory capital ratios are shown below).

Despite this relief, however, conversations I have had recently with multiple bank management teams have indicated that regulators are growing increasingly concerned with the OCI impacts on GAAP equity capital.

… so where does this leave us?

What Are Our Options Here?

Given this “conundrum” for NLB and numerous other community banks around the country, I thought it would be helpful to lay out the options (none of which are ideal) for how to move forward. Keep in mind, the backdrop that I’m assuming going forward the Fed continues to shrink its balance sheet which results in liquidity and deposits being pulled out of the system, coinciding with an inflation print that rivals the late 1970s, and the potential for a looming consumer recession.

Door 1 - Sell the Securities

This is perhaps the most obvious solution to a liquidity crunch, yet as rational as it sounds the absurdity of this solution is equally present. On the one hand, it makes all the sense in the world for a bank to decide to cut bait and liquidate its portfolio in a time of need. On the other hand, for the most part, these securities are agency-backed MBS and US Treasury Securities, which are the highest-rated credit instruments in the world. To realize a loss on a securities portfolio that for all intents and purposes bulletproof in credit quality seems asinine.

More importantly, right now the marks on this AFS portfolio are only unrealized losses and for all banks that are not systemically important to the global economy (G-SIBs) the unrealized losses don’t impact their regulatory capital ratios. The reg. cap. ratios must be kept above certain minimums for a bank to operate freely. However, if the bank decides to sell these securities and realize the losses then that hits Net Income which does get looped into their regulatory capital ratios. This would then put the bank at risk of being submitted to a consent order and thus need to be recapitalized.

Door 2 - Raise Capital

This is another obvious solution to a hypothetical liquidity crisis, however, it’s the quickest way to evaporate any investor confidence in a management team. Not only are you raising presumably dilutive, expensive capital and thus wiping out your existing shareholder base, but you also don’t solve the root of the problem because you still have this underwater securities book.

In certain circumstances, it may make sense to raise subordinated debt or preferred equity (see PACW), but again this capital is a drag on EPS and does not instill investor confidence

Door 3 - Move Available for Sale Securities to Held to Maturity

This solution is currently being widely adopted by numerous banks and ironically you can think of it as a sign of strength for the banking system more broadly. However, longer-term it can be a troublesome action if we do end up in a true liquidity crisis. The reason that it’s being widely adopted right now is banks are trying to stop the bleeding of their equity and by moving from AFS to HTM it basically locks in the losses that you have today but any future losses (or gains) do not get looped into the OCI calculation and thus to bank equity capital. Kind of funny to think about because the securities haven’t changed at all, they’re the same portfolios but just get different accounting treatment. This is troublesome for the future outlook because say we do head into a true liquidity crunch and banks need to tap into this high-quality securities portfolio, once they are moved from AFS to HTM the process to unwind this and sell these securities is very burdensome (after all they are supposed to be “Held to Maturity).

Door 4 - Pledge the Securities

I am somewhat surprised that this option is not getting more traction in this environment and it may be because liquidity is not yet sufficiently exhausted to warrant such an action. But like discussed above, bank securities portfolios in broad terms are very high quality and usually consist of Agency MBS, US Treasuries, Municipal Bonds, and, less frequently, highly rated ABS/CLO paper. These assets are primed to be pledged to the Federal Reserve or more likely the Federal Home Loan Bank for Advancement lines. These facilities exist for the exact purpose of providing liquidity on high-quality paper. This method for building a fortress balance sheet has the added benefit of not having to sell off the paper at a massive discount. Plus, the rate paid on an FHLB Advance is most likely lower than anything you could get in the sub-debt market. I wouldn’t be surprised to see this method gain more usage if we do get into a significantly tighter liquidity environment.

Conclusions

You’ll have to forgive me as this is my first long-form piece on the banks so I don’t have the best closing arguments. This article really started as a function of me wanting to just write down my thoughts and provide some color commentary on the current environment, it wasn’t originally intended to have any actionable advice. I suppose for those investors out there reading this, be cautious of any bank that has a low cash balance and large securities portfolios, even those who keep most securities in HTM are at risk in a true liquidity crisis. For any bankers reading this, however unlikely that is, the yield curve today is inverted, so you’re getting the same APY on a 2yr treasury as you are on a 10yr treasury, my recommendation would be to keep any securities purchases short duration in nature.

I thought I also had was that I don’t believe the full effect of extension risk in MBS portfolios is being priced in today. There are a lot of banks who have stated securities durations of 4-5 years on an MBS portfolio whose true duration will most likely end up being much longer. The age of mortgage refinancing is behind us for now.

One last comment I will put out there, but probably save for a future piece, is the broader effects this has on bank M&A. There are a bunch of pending bank deals out there today, and a good amount of them marked the balance sheets of the acquired entity in a different rate environment. At the same time, the regulatory approval process for bank deals is at a standstill and even seasoned acquirers that usually fall under the radar are being held up (OCFC/PTRS). It will be interesting to see how many (if any) of these acquiring banks walk away from previously announced deals, for this confluence of factors. It will also be fascinating to see how much new M&A gets announced for the same reasons.

Finally, I will leave you with a series of charts that I thought was pretty interesting to look at. The first presents the EOP marks on the AFS securities portfolios between the amortized cost basis and the fair value and pairs that against bank’s OCI. People smarter than me will know why it varied so drastically pre-2012, but as you can see since then the correlation is very tight, for obvious reasons. The second chart, however, is the more interesting one. This chart shows what the OCI impact would be if you included the marks on the HTM portfolio, look how much bigger that equity hit would be. Both charts are for all U.S. regulated depositories and use call report data.

Using this time period because it’s generally less fungible when looking at bank balance sheets and return profiles. Once you include 2020-2022 you can inflate numbers from PPP loans and fees from those loans and massive deposit growth as a result of enormous government stimulus.

Usually, I will use ROTCE (Return on Tangible Common Equity), but in this case, the bank has few intangible assets so ROE is easier and ubiquitous among the investing community.

This is because the core value of a bank is determined by two things: first is a bank’s ability to accurately price through-the-cycle credit risk and second is a bank’s ability to generate low-cost core deposits. Many people will talk about returns and capital efficiency, but without these credit quality and low-cost deposits, a bank is doomed from the start.

There are obviously caveats to this that include, among other things, higher credit costs associated with loans, higher operating and fixed expenses, and lower liquidity in loans versus cash or securities, however, if done right the higher yields and related fee income from loans outweigh these costs.

Thanks for doing this writeup. I'm fairly new to bank stock analysis so I didn't totally follow everything, but it was very helpful seeing a lot of terms I've been learning put into practice. Great work, and I hope you'll write more!

What a great write up. Thank you for sharing all your research truly excellent.